Treaty Education (Jennifer Tupper)

My research/scholarship/teaching in Treaty Education began after I arrived at the University of Regina in 2004. As a former high school social studies teacher in Edmonton, then a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, I thought I brought a critical lens to my teaching and research, and in some respects I did. However, when I was invited to participate in a research project exploring best practices in treaty education, supported by the Office of the Treaty Commissioner and the Ministry of Education in Saskatchewan, I realized the limits of my knowledge. Not once as a teacher or graduate student had I considered the significance of the numbered treaties to the foundational history of Canada. This is not part of the officially sanctioned story of the nation, nor was it part of my historical consciousness as a Canadian. However, the partnership between First Nations people and non-First Nations people in Canada has been an integral, and arguably the most important, part of the history of this country. The numbered treaties entered into by First Nations and the British Crown exemplify these partnerships. They made possible the opening up of vast tracts of land for European settlement. As historian J. R. Miller asserts in Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (2009), treaties are one of the “paradoxes of Canadian history. Although they have been an important feature of the country since the earliest days… relatively few Canadians know about or understand what they are or the role they have played in the country’s past” (p. 3).

In my scholarship and research, I am troubled about this not knowing, particularly as I explore the historical and contemporary significance of treaties and the treaty relationship. Through my research with teachers, students, and teacher candidates, I continue to examine how social and economic privileges for white settlers living and working on the prairies are directly connected to the treaties. I engage with anti-colonial/decolonizing pedagogies in education, and draw on the wisdom and stories of First Nations elders in an effort to ‘unsettle’ dominant knowledge and identities. Becoming involved in that first treaty education research project was revelatory for me. From it, my co-researcher Michael Cappello and I wrote “Teaching Treaties as (Un)usual Narratives: Disrupting the Curricular Commonsense” (Curriculum Inquiry 38[5] [2008]: 559-78) which received the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies Outstanding Publication Award. In the article we argue that treaty education is necessarily disruptive to dominant narratives of the nation and the Eurocentric curriculum that reproduces these narratives. Thus, treaty education is both a productive and interrogative site of learning. It is an example of a curricular initiative that has the potential to invite students to think deeply and differently about the history of Canada and themselves as citizens by challenging colonial blind dispositions, as discussed by D. Calderón in “Locating the Foundations of Epistemologies of Ignorance in Education Ideology and Practice” (in Epistemologies of Ignorance in Education, edited by E. Malewski and N. Jaramillo, 2011). To be clear, treaty education is much more than teaching the content of the numbered treaties. It invites teachers to integrate historical and contemporary stories, knowledge, and experiences of First Nations people, including those deeply connected to colonialism. It necessitates critical inquiry of treaty promises and the corresponding failures, past and present, on the part of the Government of Canada to uphold these promises.

Because treaty education is a mandatory curriculum initiative in all grades and across all subjects in Saskatchewan schools, my research has explored the limits of teacher candidates’ knowledge and understanding of treaties and the treaty relationship, their sense of preparedness to implement the mandate in their own classrooms, and the ways in which our Faculty of Education might better integrate treaty education into our teaching and learning. I draw on scholars’ writing about epistemologies of ignorance to make sense of the ongoing resistance to treaty education that emerges in conversations with educators who prefer not to embrace the initiative.

Because treaty education is a mandatory curriculum initiative in all grades and across all subjects in Saskatchewan schools, my research has explored the limits of teacher candidates’ knowledge and understanding of treaties and the treaty relationship, their sense of preparedness to implement the mandate in their own classrooms, and the ways in which our Faculty of Education might better integrate treaty education into our teaching and learning. I draw on scholars’ writing about epistemologies of ignorance to make sense of the ongoing resistance to treaty education that emerges in conversations with educators who prefer not to embrace the initiative.

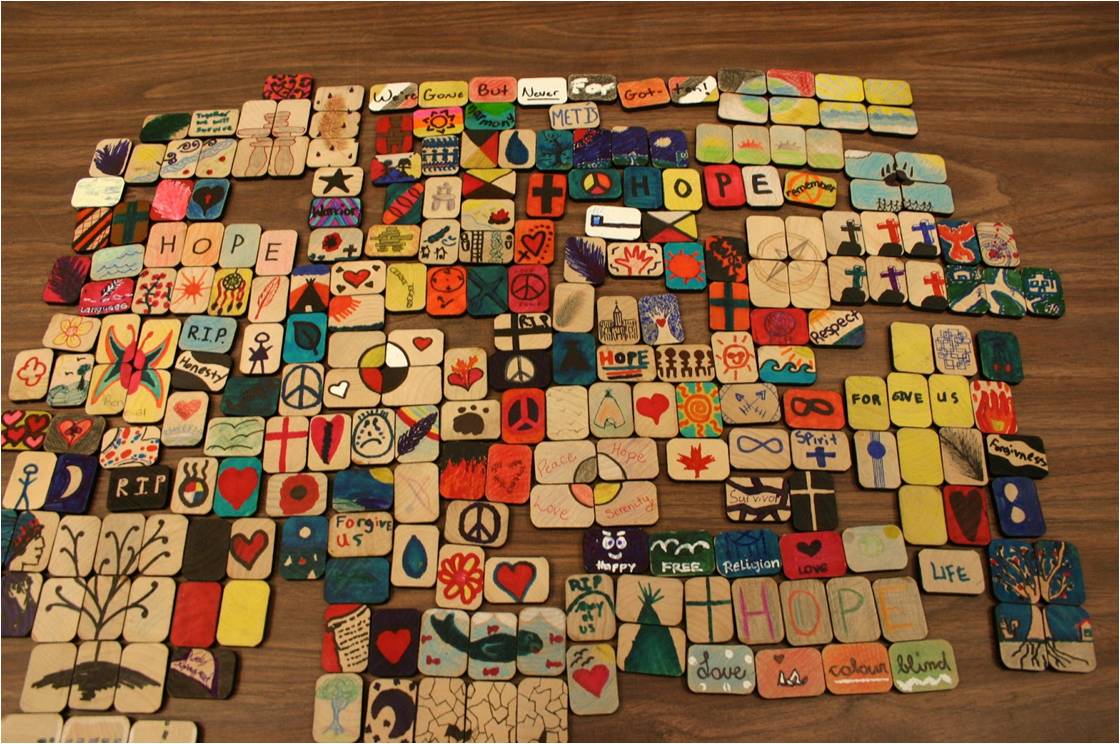

Most recently, with a team of researchers, I have completed a SSHRC-funded research project titled “Storying Treaties and the Treaty Relationship: Enhancing Treaty Education through Digital Storytelling.” In this project, we worked with four elementary classroom teachers and their students over two years to create digital stories highlighting their learning about treaties and the history of Aboriginal-Canadian relations. These children responded with some amazing narratives about what it means to be a treaty person. One of our teacher participants created a website We are all Treaty People: An Ongoing Quest to Bring Treaty Education to the Classroom, and I encourage you to visit it to see firsthand the value of treaty education.