Teaching and Learning in the Eighteenth-Century Northeast (Thomas Peace)

Rather than telling you about myself, I want to introduce you to my friend Louis Vincent, or Sawantanan as he was known at home. Louis was the first schoolteacher in his community and, quite likely the first Native schoolteacher in what would later become Canada.

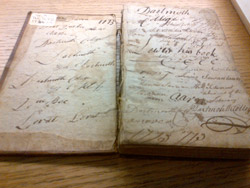

Louis was an extraordinary individual. Born in a Wendat community near the town of Québec in the 1740s, Louis’ adolescence was marked by military conflict and regime change. In the early 1770s he left home to attend Moor’s Indian Charity School, and later attended Dartmouth College. Soon after arriving at this ‘college in the woods’ in rural New Hampshire, the Revolutionary War broke out. Louis spent the war serving as an interpreter for the Continental Congress, even meeting George Washington during his service. As the war waned, he returned to his schooling, graduating from Dartmouth in 1781. With his studies complete, he joined the Anglican missionary John Stuart and the Mohawk on the shores of the Bay of Quinte. With Stuart, Louis ran a school and helped translate the Bible into Mohawk. In 1791, he returned home to open a day school. There he taught the village’s children until he died in 1825.

I first met Louis while researching my doctoral dissertation on how Native people experienced the conquests of Acadia and Canada. When I compared the Wendat near Québec and the Mi’kmaq living around Annapolis Royal, Louis fascinated me. Not only did he interpret between the Mi’kmaq, Penobscot and American delegates during the Revolution, but also a man named ‘Vincent’ led a Wendat war party that attacked Annapolis Royal in 1745. Although these communities experienced European regime change in radically different ways, and I do not know if these two Vincents were related, my friend Louis stitched these places together. He encouraged me to think more deeply about the interconnected nature of the places we know today as Québec, New England and Maritime Canada, a key theme as I rework my dissertation into a book.

Over the past year and a half I have come to know Louis much better. Last October my family and I moved down to Hanover, New Hampshire, home to Dartmouth College. I was there to begin my postdoctoral research on Louis and others like him. Although Louis was one of only a handful of Native people to graduate from a colonial college, there were about seventy similar students between 1760 and 1830 who came to Moor’s Indian Charity School and Dartmouth College from Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) territory or Native communities in the St. Lawrence valley. Several of these students followed Louis’ path, returning to their communities to open some of the first schoolhouses in their region.

Over the past year and a half I have come to know Louis much better. Last October my family and I moved down to Hanover, New Hampshire, home to Dartmouth College. I was there to begin my postdoctoral research on Louis and others like him. Although Louis was one of only a handful of Native people to graduate from a colonial college, there were about seventy similar students between 1760 and 1830 who came to Moor’s Indian Charity School and Dartmouth College from Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) territory or Native communities in the St. Lawrence valley. Several of these students followed Louis’ path, returning to their communities to open some of the first schoolhouses in their region.

We know very little about the history of education during this period. In the United States, the focus on Native people and colonial structures of education ends with the Revolution. In Canada, attention is placed on early religious endeavours in seventeenth-century New France or the later development of residential schools. Taken together, a gap remains between the 1780s and 1830s.

My journey with Louis suggests that this gap needs to be filled with greater attention paid to the diverse peoples living in northeastern North America.