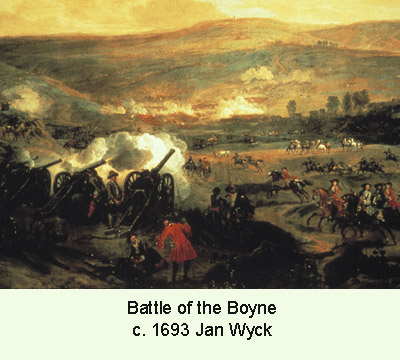

The Politics of History Education: from the Battle of the Boyne to Chairman Mao (Tony Taylor)

It was Brother Richard of De La Salle Preparatory School, Pendleton, Manchester (UK) who inadvertently acquainted me, at the age of eight, with the connection between history education and ideology, a connection that has, in the past decade or so, been a dominant theme in my research. Brother Richard taught us his own Catholicised version of the 1690 Battle of the Boyne, and this is it. On one side of the Boyne River (a muddy creek, in reality) stood the forces of the deposed Catholic King James VII, who still claimed the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland. Facing him was the army of the Protestant incumbent, Prince William of Orange. According to Brother Richard, the battle, and the cause of Catholicism in Ireland for the next two centuries, was lost when, freakishly, a Williamite cannon ball took off the head of the only Jacobite general who knew the plan of battle. In consequence of this misfortune William triumphed, James fled into exile - and the post-conflict, commemorative Orange Order is still with us today. In actuality, the battle was a bit of a muddle and the Jacobites retreated in the face of a more professional Williamite force. But it was not just Brother Richard who tweaked historical narratives to suit his own viewpoint. In college (senior high school) we were later taught that Henry VIII actually died a good Catholic and that Elizabeth I recanted her mistaken Protestant ways on her deathbed, unusual historical assertions then and now.

It took quite a while for me to journey from a forsworn Elizabeth to more recent examples of the relationship between ideology and the ownership of historical narratives. My next enlightenment came much, much later, in 1999, when the Liberal National Party (LNP – conservative coalition) federal government in Australia set up a national inquiry into history in schools and I was fortunate enough to lead the Monash University team that conducted the survey. As a consequence of that inquiry, from 1999 onwards, I have been closely involved in successive federal LNP and Australian Labor Party (ALP) initiatives in history education and they have taught me the following: first, conservative politicians value history education with much greater intensity than do their Labor counterparts. The latter will give a dutiful but inattentive nod to the importance of history. The ALP is much keener on literacy, numeracy, career-friendly curriculum subjects and laptops in every classroom. Labor has been, and in practice remains, perfectly sanguine about banishing history education to the margins of the school curriculum.

The contrasting emphasis that conservatives place on the importance of history education is largely based on a belief that history in the classroom should celebrate the national story through knowing (rather than understanding) a master narrative of a (Burkean/Whiggish) organically developing parliamentary democracy, a narrative based on unassailable political and economic facts. To give you an example of what I mean by this, here is another story. In late 2006, I was in the ministerial suite in Canberra, sat across the table from two black-suited LNP advisers who were peering at a draft (inquiry-based, conceptually organised, open-ended) history curriculum framework I had prepared for their minister. “We’d like to see more particularities,” one of them said. “Do you mean more facts?” I asked. They shifted in their seats, and nodded. “And more political and economic history” said the other. My response was that the full range of high school students generally disliked political and economic history but did respond well to social history. Good teachers could use social history as an inquiry-based avenue to exploring political and economic issues. They looked at me as if I were quite mad. They could not comprehend the notion of student inquiry in history classes - and social history smacked of socialism.

Which brings me to the second thing I have learned which is that, as a rule, conservative politicians suspect continuing Leftist infiltration of the history classroom and they see progressive history education as a radical activity carried out by seditious history teachers. It was certainly the case that during the 2006-2007 national debates on Australian history education, the term ‘Maoist’ was bandied about with wild abandon by the then LNP education minister and her advisers.

Which brings me to the second thing I have learned which is that, as a rule, conservative politicians suspect continuing Leftist infiltration of the history classroom and they see progressive history education as a radical activity carried out by seditious history teachers. It was certainly the case that during the 2006-2007 national debates on Australian history education, the term ‘Maoist’ was bandied about with wild abandon by the then LNP education minister and her advisers.

This obsession with the politicised nature of what is assumed to be happening in history classrooms explains some of the intensity that the conservative side of politics displays about history in schools, especially in Grades 9-10, the final years of compulsory education. The fervent hope of my black-suited advisers was that they could wield influence in the classroom with an ideologically-framed form of school history that would act as a prophylactic against the incursions of more reflexive, discursive (and consequently subversive) forms of history. In other words, incontestable and celebratory facts are intended to drive out complex, contested themes and thoughts.

In this vein, the latest research trip that I, and research associate Sue Collins, have undertaken is a study of the influence of the conservative press on history education in Australia. It makes for fascinating reading: “The Politics are Personal: the Murdoch Press, a Culture of Intimidation and the Australian History Curriculum,” The Curriculum Journal (forthcoming).

Tony Taylor teaches and researches at Monash University, Victoria, Australia. From 2001-2007 he was director of the federal National Centre for History Education, a THEN/HiER partner organization. He is currently working on two Australian Research Council history projects: one is on early years national curriculum implementation in Australia, and the other is a comparative project on senior school implementation in Australia and in Russia. Sue Collins is an Assessment Research Centre (ARC) research officer at Monash University.