My Scholarly Passions (Margaret Conrad)

Like many women of my generation, I fell into a career in history. Only one of my university professors was a woman—she taught French language classes—so I never imagined myself in such a position. After achieving an MA in history at the University of Toronto, I entered the paid labour force in 1968 as a textbook editor for Clarke Irwin. With universities expanding at an unprecedented rate, I received an unsolicited invitation in the summer of 1969 to teach history at Acadia University where I had pursued my undergraduate degree. After a rough fall term lecturing on Canadian, Western Civilization, and British Empire and Commonwealth history to large numbers of students, I discovered that I had a knack for teaching. I soon embraced two scholarly passions: Atlantic Canada history and Women’s Studies, fields that developed in response to political movements in which I was deeply engaged.

For me and other young academics caught up in what was called “the new social history,” our research was intensely relevant and often of great interest to the general public. One collaborative project resulted in the book (co-authored with Toni Laidlaw and Donna Smyth) No Place Like Home: The Diaries and Letters of Nova Scotia Women, 1771-1938 (Formac, 1988), which sold more than 8,000 copies, a best-seller in Canadian terms. As an academic with editorial experience, I became a co-founder in 1975 of Atlantis, a journal devoted to the new interdisciplinary scholarship on women. The collaborative approach typical of Women’s Studies was mirrored by Atlantic Canada specialists, who founded the journal Acadiensis in 1971. Since established journals were inclined to discount “regional” history, Acadiensis and Acadiensis Press served as the major outlets for my research on the political economy of the Annapolis Valley, political cartoonists, and several edited volumes on New England Planters, a group of 8,000 forgotten immigrants who settled in the Maritimes before the American Revolution.

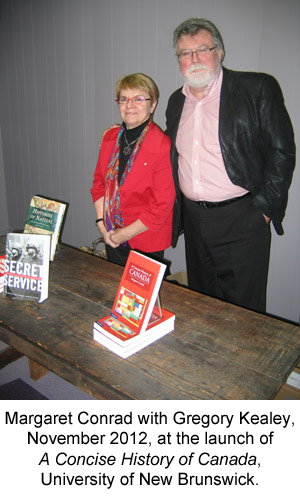

By the early 1990s, I was keen to bring the new academic research on women and Atlantic Canada to university textbooks. Counting the various editions of History of the Canadian Peoples (with Alvin Finkel and now Donald Fyson), I have co-authored 16 versions of Canada’s story, clear testimony, if any were needed, that history is an ever-changing narrative. The appearance in 2012 of A Concise History of Canada (Cambridge University Press), is the culmination of my textbook writing career, which also included three editions of Atlantic Canada: A History (Oxford University Press ), co-authored with James Hiller.

By the early 1990s, I was keen to bring the new academic research on women and Atlantic Canada to university textbooks. Counting the various editions of History of the Canadian Peoples (with Alvin Finkel and now Donald Fyson), I have co-authored 16 versions of Canada’s story, clear testimony, if any were needed, that history is an ever-changing narrative. The appearance in 2012 of A Concise History of Canada (Cambridge University Press), is the culmination of my textbook writing career, which also included three editions of Atlantic Canada: A History (Oxford University Press ), co-authored with James Hiller.

When I was awarded a Canada Research Chair in Atlantic Canada Studies at the University of New Brunswick in 2002, my research took dramatically new directions. I used some of my funding to bring together the Canadians and Their Pasts collective (principal investigator Jocelyn Létourneau), which secured SSHRC funding to conduct a survey on how Canadians engage the past in their everyday lives. A book based on this research is forthcoming from the University of Toronto Press. I also worked with technicians associated with UNB’s Electronic Text Centre and a great many student assistants to explore the potential of humanities computing through the Atlantic Canada Portal and the Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives.

Riding two very ambitious research horses was exhilarating but also exhausting, prompting me to take early retirement in 2009 to devote more time to writing. I am currently working on a history of Nova Scotia and involved in another humanities computing project, this one comparing the vocabularies of identity in anglophone and francophone New Brunswick.

As the foregoing attests, old historians never give up doing research, they just find new projects to inspire their energies.