Landscapes and Mindscapes: Engaging Indigenous Research and Researchers Historically (Michael Marker)

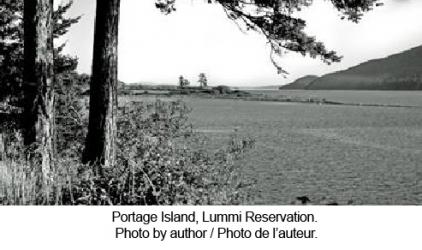

My work in the history of education has been like a Coast Salish canoe journey through time and space. In the Salish cosmologies it is important to make perennial visits to locations on the landscape that hold stories of potent cultural and mythic meaning. At the same time that people made trips to reacquaint themselves with the storied past as animated by significant rocks, mountains, glaciers and other points of reference in their world, they also visited villages and participated in ceremonies that included ancient references to changes in landscapes and resources such as fisheries or other food harvesting sites. I have traveled throughout the borderless Coast Salish region not only listening to what Aboriginal people say about their experience with education—broadly conceived—but also trying to analyze the discourse of the settler society regarding their interpretations of the history of the colonization of Indigenous peoples. Much of my studying has looked at the reality of residential schools and conditions in institutions of higher education, but I have also been drawn to write about methodologies for inquiring into the meaning of the past from a cross-cultural perspective.

In some respects, I have been more interested in non-Indigenous settler societies than in the Native people and Aboriginal communities. As an Indigenous scholar, I have been more interested in the “Others that Other us.” I have tried to look at conventional educational discourse and practice from the perspective of Indigenous values and interpretations. My most recent work is examining the nature of research from an Indigenous perspective. In other words, I am researching the “culture of research” and the properties of the history of research and researchers in the Coast Salish region. What are the conversations between researchers and Aboriginal peoples? What are the missing conversations? What are the values, beliefs, and approaches of researchers who are often eager to venture into an Indigenous community to talk with elders, but then neglect to consult the work of Indigenous scholars who have attained PhDs and might offer fundamental challenges to the interpretations, goals, and desires of the researchers? The title of one of my most successful articles is telling in this regard: “Indigenous Voice, Community, and Epistemic Violence: The Ethnographer’s ‘Interests’ and What ‘Interests’ the Ethnographer.” I have chosen to perform research between the disciplines of both anthropology and history in order to gain from each field’s capacities to explicate culture and educational change.

These questions are not my own questions exclusively. They are part of a long academic history of critique and complaint from Indigenous scholars beginning with Vine Deloria’s well known chapter, “Anthropologists and Other Friends,” in his iconic/iconoclastic Custer Died For Your Sins. In Indians and Anthropologists: Vine Deloria, Jr. and the Critique of Anthropology, Indigenous scholar Cecil King makes a strong argument that Indigenous communities should have the right to not be researched—as opposed to social scientists’ right to know (italics mine). Furthermore, in the Coast Salish region, specifically, I have listened to many community narratives about university researchers’ conduct. The explication from Elders and traditional knowledge specialists are resonant with Jo-ann Archibald’s (1999) essay critiquing the conduct of anthropologist Crisca Bierwert in the Sto:lo communities of the Fraser Valley. I have very practical reasons and questions for engaging in this kind of inquiry. What are the underlying cultural and methodological assumptions; the animating goals of social science researchers of all sorts that perform research in Indigenous communities? How can these questions be answered from what the researchers say about themselves to the communities and through their research practices and findings? What can be done to support the ability of Indigenous communities to discern, differentiate and respond to research that perpetuates a history of invasion and resource extraction by ethnocentric academics, versus research that brings potential benefits such as university/community collaborations and reciprocity?