Exploring Classroom Perspectives on the Past (Amy von Heyking)

I was in Grade Five when I first understood the challenge for many people of coming to terms with multiple perspectives on the past, when I realized that the stories about my family’s history did not have a place in the classroom. My teacher was leading a discussion about the importance of Remembrance Day and she asked if any of us had family members who had participated in the Second World War. I said that my father had been captured in North Africa and spent most of the war in prisoner-of-war camps in Louisiana and Texas. My teacher said, “But Amy, the Americans were our allies.” I responded, “I know. My relatives fought on the German side.” There was silence for what seemed like an eternity, and then my teacher said, “Oh. We all make mistakes.”

So, like many students, I learned that there were at least two stories about the past that were essentially irreconcilable: there was the national story, a “master narrative” about Canada’s past that we learned in school; and there was my family story. The master narrative was interesting, but it wasn’t very meaningful. There didn’t seem to be a place for me to “fit into” that story. Much of the research I have done in the history of school curriculum and history teaching has been a result of that early insight that the historical perspectives presented in school curriculum not only reflect our identity, but also shape our identity. In my scholarly research, I have posed questions that were provoked by that fifth grade episode and by my experiences as a social studies teacher: whose stories have we included in school curriculum? How was school curriculum created and implemented? How did schools shape our understanding of national identity? What impact did the perspectives presented in school curriculum have on the learning experiences of children?

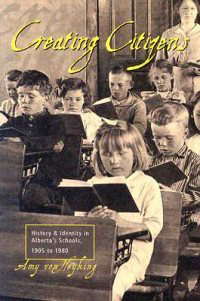

In Creating Citizens: History and Identity in Alberta’s Schools, 1905 to 1980 (University of Calgary Press, 2006), I explored the changing nature of citizenship education in the province. I was particularly interested in the way the school curriculum embodied messages about the province’s unique regional identity, as well as evolving understandings of Canadian identity. I also addressed how and why the province, led by relatively conservative governments, endorsed very progressive social studies programs. Since then, I have published articles that examined the images of Americans in Canadian curriculum and textbooks, and the nature and impact of notions of “Britishness” in Canadian schools in the 20th century.

In Creating Citizens: History and Identity in Alberta’s Schools, 1905 to 1980 (University of Calgary Press, 2006), I explored the changing nature of citizenship education in the province. I was particularly interested in the way the school curriculum embodied messages about the province’s unique regional identity, as well as evolving understandings of Canadian identity. I also addressed how and why the province, led by relatively conservative governments, endorsed very progressive social studies programs. Since then, I have published articles that examined the images of Americans in Canadian curriculum and textbooks, and the nature and impact of notions of “Britishness” in Canadian schools in the 20th century.

In all my work in curriculum history I have attempted not just to analyze the official curriculum in programs of study and textbooks, but also to explore how that curriculum was communicated to and experienced by students in classrooms. Teachers have always negotiated and even challenged curriculum reforms, adopting or adapting new programs to suit the needs of their students and their own contexts and values. It is an enormous challenge for historians to understand curriculum beyond the rhetoric of official programs of study and within the reality of classrooms. Rare primary sources, such as students’ schoolwork and teachers’ planning materials, help me address what historians have called the “black box” of curriculum history, i.e., The Classroom. My current research project examines the extent and nature of the implementation of child-centred, progressive innovations in schools.

I have also begun to research how students grapple with history instruction that allows them to explore multiple perspectives. The Alberta Program of Studies in Social Studies requires that teachers facilitate students’ understanding of diverse and often conflicting perspectives of people in the past. There is, however, limited research to indicate the extent to which children can understand and articulate the perspectives of the people of another time and place. My study of sixty Grade Four students explored the basic characteristics of their expressions of historical empathy, and assessed the impact of specific instructional strategies such as novel studies on their ability to articulate a range of historical perspectives. The students initially demonstrated all the presentist assumptions other researchers have found. Over the course of the school year, the students explicitly engaged with the concept of historical perspective, researched their family history, and completed a range of learning activities about their community’s and the province’s past. At the end of the year, they still struggled with some perspectives, particularly those they had encountered in novels rather than informational text. Students grew in their ability to articulate historical perspectives, but their ability was affected by their emotional development, the specific historical topic they were studying, even specific events in their own lives. While there is no question that history instruction that attends to a range of perspectives is challenging for students, I believe that it is key to nurturing attentive, respectful, responsible and caring citizens.