Encounters with Heritage: Tensions between Familiarity and Strangeness (Maria Grever)

Seeing ‘things as they are,’ Carlo Ginzburg has written, requires a balance between coming so close to an object that it seems familiar and moving so far from it that the distance deconstructs any feeling of familiarity. This tension between closeness and distance, between familiarity and strangeness, is what strikes me about the use of what we call ‘heritage’ as an educational resource for history teaching. Museums often emphasize the proximity pole and promise a complete immersion in the past. They argue that students appreciate historical objects, imaginative sounds and video clips. Walking through multimedia museums would offer them a sensory experience through which they might better understand the evoked past. Indeed, heritage in its public manifestations appeals to direct experiences, emotions and veneration. What does this mean when the use of heritage features prominently in history teaching?

In his famous book The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (1998), David Lowenthal stresses the uncritical and patriotic aims of heritage. Yet in the academic field of heritage studies a dynamic approach to heritage dominates the growing body of research. The research concentrates for instance on critically examining the uses of heritage to construct local and national identities, on the performative character of museums and the darker sides of heritage. Laurajane Smith, Peter Aronsson, Willem Frijhoff and others explain that traces of the past are not just ‘found.’ Heritage is a constructed medium, a performative action and a process of re-mediation, embedded and mobilized in various cultural contexts. Hence, studying heritage is to understand the shaping of identities and the power of culture. This dynamic view supports the longstanding trend in the Netherlands on developing historical thinking skills in history education. From this viewpoint, the use of heritage can motivate students to question the aims and contexts of objects, monuments and sites.

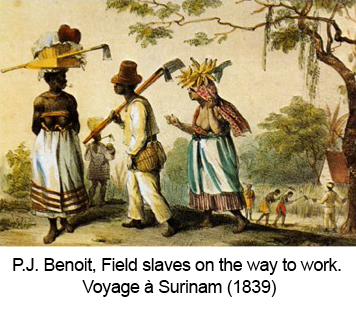

These critical heritage studies have also influenced the research program Carla van Boxtel and I are now finalizing: Heritage Education, Plurality of Narratives and Shared Historical Knowledge (2009-2014). In our research, ‘heritage education’ points to teaching and learning settings in which material and immaterial traces of the past are used as primary instructional resources to strengthen students’ understanding of history. In three research projects involving history teachers and museum educators, 12-18 year-old students, and heritage educational resources, we have investigated existing heritage education practices, in particular regarding the possibility of applying historical thinking concepts such as multiperspectivity and significance. We focused on two sensitive topics: Transatlantic Slave Trade and World War II / Holocaust. Apart from synthesizing theoretical reflections and empirical outcomes, we will formulate benchmarks for the integration of dynamic and professional heritage education in the curriculum of Dutch secondary schools.

A fascinating concept in this research is historical distance, which I consider as a varying configuration of temporality, spatiality and engagement. Temporality refers to synchronic or diachronic approaches to the past. Spatiality points to the spatial distance from people to a heritage site where historical events have taken place. Engagement implies the degree of affection, moral commitment and identification with the past. The three levels are intertwined and expressed in rhetoric, narrative plotlines and mnemonic bridging techniques, also studied by Eviatar Zerubavel and Pieter de Bruijn. For instance, synchronic approaches might generate a sense of sameness with the past located on a specific site, illustrated by engaging statements such as ‘our ancestors in the prehistoric age’ who constructed dolmens on the same place where we live now. Diachronic approaches often emphasize continuity and progress, expressed in rise-and-fall-plots, accompanied by stories about pilgrimages, diasporas and the return to the homeland. These and other reflections on historical distance are important for educators. The emphasis on experiencing the proximity of the past that many museums promise to visitors enhances the idea of sameness between past and present. This identification approach tends to deny historical reality as reality, inducing a complete misunderstanding of the past. Moreover, this sameness not only disturbs the temporal orientation resulting easily in anachronisms, but it also impedes the acknowledgement of other perspectives. Living the past as the present and vice versa blocks an open mind. If the past is everywhere, it is hard to discover new viewpoints. Then it is also impossible to construct shared historical knowledge.

A fascinating concept in this research is historical distance, which I consider as a varying configuration of temporality, spatiality and engagement. Temporality refers to synchronic or diachronic approaches to the past. Spatiality points to the spatial distance from people to a heritage site where historical events have taken place. Engagement implies the degree of affection, moral commitment and identification with the past. The three levels are intertwined and expressed in rhetoric, narrative plotlines and mnemonic bridging techniques, also studied by Eviatar Zerubavel and Pieter de Bruijn. For instance, synchronic approaches might generate a sense of sameness with the past located on a specific site, illustrated by engaging statements such as ‘our ancestors in the prehistoric age’ who constructed dolmens on the same place where we live now. Diachronic approaches often emphasize continuity and progress, expressed in rise-and-fall-plots, accompanied by stories about pilgrimages, diasporas and the return to the homeland. These and other reflections on historical distance are important for educators. The emphasis on experiencing the proximity of the past that many museums promise to visitors enhances the idea of sameness between past and present. This identification approach tends to deny historical reality as reality, inducing a complete misunderstanding of the past. Moreover, this sameness not only disturbs the temporal orientation resulting easily in anachronisms, but it also impedes the acknowledgement of other perspectives. Living the past as the present and vice versa blocks an open mind. If the past is everywhere, it is hard to discover new viewpoints. Then it is also impossible to construct shared historical knowledge.

Recently, I worked with some colleagues on a large-scale European proposal regarding popular encounters with war heritage that evoke fierce public debates in relation to the risks of banalising history and the circulation of distorted knowledge. These controversies reveal the growing contrast between the often uncontrollable popular initiatives and the institutionalised commemorative practices of acting in a respectful way. In this research I will explore the tensions between familiarity and strangeness again, but this time in the context of popular historical culture and city branding.