Do Media Teach the Past? (Scott Alan Metzger)

My high-school history teacher showed Becket (1964) in class. I loved the film but was surprised to learn (when I studied the source play in college) that Thomas Becket really wasn’t Saxon like in the movie. Nonetheless, I still felt like I gained something from watching this film—I was certainly more interested in medieval history because of it. Was that why my teacher chose to show Becket in his class, or did he (mistakenly) think it was accurate, or did the film’s theme of moral resistance to tyrannical authority resonate with his politics in the 1980s?

When I became a high-school teacher, I brought my love of history movies into my classroom. Most of my students were equally excited—especially teenage boys, as this was the era of Saving Private Ryan (1998) and Gladiator (2000). I had a sense that my students would gain some educational benefit beyond just excitement or visual interest, but I grew uncertain upon learning the hard way how unreliable history movies tend to be in terms of factual accuracy. My experience as a novice practitioner using film was unfulfilling. When completing my Ph.D., I discovered a growing domain of research on history and popular culture. Alan Marcus introduced me to a community of scholars interested in educational uses of history films by inviting me to contribute to his edited book Celluloid Blackboard: Teaching History with Film (Information Age Publishing, 2006).

So after a doctorate, a decade of study, and a number of publications, what have I learned in response to the question, “Do media teach the past?” My answer is—yes, but not very well on their own. It is clear that mass media are highly influential on the general public, including students. Pretending that media influence doesn’t affect students’ academic learning isn’t a satisfying option. Even when students are savvy enough to acknowledge that media are not always historically accurate, they often don’t know how to distinguish fact from fiction. Images and messages in media can colonize the memory and imagination—an impact on historical thinking that may be only semi-conscious. The view that media by themselves “teach” the past is highly problematic, as any educational effects frequently are ancillary to the film’s goals. A well-prepared, knowledgeable teacher is required to help students view historically oriented media critically and analytically, not just as entertainment. Students learn from media best when they have educative questions to think about and activities to apply what they learn.

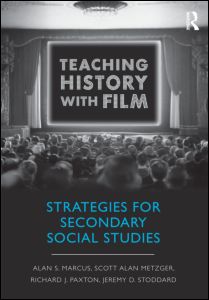

One major conclusion emerging from my work with teachers and other scholars interested in history and media is the importance of instructional intentionality. Picking the right media title is not enough (though that helps). A really good historical movie can be badly used in the classroom, and a historically bad movie can be put to good educational use. The key is to have planned instruction and scaffolding that positions students to engage meaningfully with media for clear learning purposes. Alan Marcus, Rich Paxton, Jeremy Stoddard and I demonstrate such purpose in Teaching History with Film: Strategies for Secondary Social Studies (Routledge, 2010). Through actual classroom examples, we explore techniques that support advanced learning goals like historical empathy, analytical/interpretive thinking, debating controversial issues, and history films as visual narratives.

One major conclusion emerging from my work with teachers and other scholars interested in history and media is the importance of instructional intentionality. Picking the right media title is not enough (though that helps). A really good historical movie can be badly used in the classroom, and a historically bad movie can be put to good educational use. The key is to have planned instruction and scaffolding that positions students to engage meaningfully with media for clear learning purposes. Alan Marcus, Rich Paxton, Jeremy Stoddard and I demonstrate such purpose in Teaching History with Film: Strategies for Secondary Social Studies (Routledge, 2010). Through actual classroom examples, we explore techniques that support advanced learning goals like historical empathy, analytical/interpretive thinking, debating controversial issues, and history films as visual narratives.

My hope is that scholarship like this can establish historical media literacy as a recognized skill in social education and teacher training. History is not just academic—the past is also a source for making sense of the world, and for how people and communities define their social identities. Being “literate” in identifying and critiquing media messages about how the past connects to the present world is a 21st-century skill if I’ve ever heard one.

While movies are a prime media form for dealing with historical topics, in recent years I’ve become just as intrigued by other media forms—such as music that includes meaning-making about the past, and video games that empower people to play in the past and encounter alternate versions and experiences. Now I am serving as lead editor of a forthcoming research Handbook of History Teaching and Learning (to be published by Wiley-Blackwell tentatively in early 2018). It will be exciting to have separate full chapters on Film, Media, and Popular Culture as well as Digital Simulations, Games, and Technology. Research on media and historical thinking and learning is rapidly growing, as is consensus in the educational community that this is a crucial issue for citizens living in a media-saturated age.