Capturing the Historical Consciousness of Young People (Jocelyn Létourneau)

I can’t boast that I’ve had many good ideas in my life. I can only think of five: my four children (ideas shared and achieved with my wife!) and then another (let’s hope it’s not the last!), that arrived late, but which I’ve been excited about since I managed to solidify it in the form of a research project.

I have always been fascinated by young people – by their intelligence, curiosity, and thirst for knowledge. I have always been disconcerted by those who claim, to the contrary, that young people don’t know much. The fact is that young people know a lot of things, but we don’t always know the best way to elicit what they know. For example, can we conclude that, since 95% of young people in Québec don’t know who the first premier of the province was, that their knowledge is deficient? We can’t, but we do anyway!

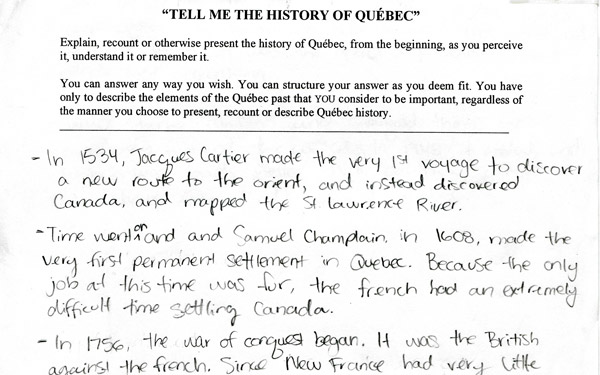

In order to counter such a simplistic methodology and interpretation, I told myself that, to get at the wealth of knowledge that young people in Québec have about their province’s history in a less superficial fashion, and to directly access their historical memory of Québec, it would be interesting to ask them a broader question, which was in this case: “Tell me the history of Québec as you know it, from the beginning.”

Over the past ten years, with the support of many teachers and professors, I gathered close to five thousand short historical accounts from young people aged from about 15 to 25 years old, from all over the province. The corpus is as massive as it is rich, consisting of texts written by young francophones, anglophones, allophones and aboriginals.

Needless to say, the accounts – all anonymous – can be analyzed by the age of the respondents or their academic level (secondary, college, university), gender, place of residence (Montréal, Québec City, other regions), language of instruction, culture of origin, etc. The accounts can also be dissected according to their constituent elements (individuals cited, events mentioned, contexts developed) and their dynamic structure (principles of construction and progression of the narrative).

Needless to say, the accounts – all anonymous – can be analyzed by the age of the respondents or their academic level (secondary, college, university), gender, place of residence (Montréal, Québec City, other regions), language of instruction, culture of origin, etc. The accounts can also be dissected according to their constituent elements (individuals cited, events mentioned, contexts developed) and their dynamic structure (principles of construction and progression of the narrative).

An analysis of the corpus allows us to grasp the level of knowledge that young people have of their past better than traditional surveys would. It especially allows us to capture the historical memory that secondary, CEGEP, and university students have of the Québecois experience over time. We believe that in the 45 minutes they were allocated to produce their account, the young people mobilized the crucial aspects of their knowledge of Québec history. Whether they wrote three paragraphs or three pages, they sculpted a timeline articulating their representation of the province’s past. In fact, it is not simply young people’s historical memory that the accounts reveal, but also their historical consciousness, their intellectualization of the ensemble of historical information relevant to Québec that they have learned, assimilated, comprehended and appropriated, in class or elsewhere, since they were young children.

This innovative approach to research has generated interest among other researchers who have borrowed it and adapted it to meet the specific requirements of their own research projects. French, Catalan, Swiss and German colleagues are currently amassing student accounts in order to better understand how history contributes to a common understanding of the constitution of a national memory. A similar research strategy may soon be launched in English Canada.

What should we expect from these types of projects? Working from the corpus of young people’s accounts, the project will allow significant progress in the study of the following: the historical memory of young people, social contexts of learning, current cultural narratives in Québec society and their assimilation, the influence of history courses in the development of students’ collective historical consciousness, the construction of historical representations, and social frameworks of collective memory in Québec – and, by implication, in Canada. The project will have an impact on history education (how to teach history, what content to deliver, which competencies to transmit). It will allow us to better understand how human beings, at the pivotal moment of passing from adolescence to adulthood, anchor their unique identities to collective visions circulating within the public sphere. It will enrich the discussion of the place of history in the present and future of society.