“Right Place, Right Time”?: Six Tips for Landing a Museum Job after Your Grad Degree That Really Work

19 August 2015 - 3:50pm

Last fall I successfully defended by doctoral thesis, got married and moved across the continent—all within a matter of weeks. I’m happy to report that America has been quite kind to me: I now have an intimate knowledge of the vagaries of the Los Angeles Metro system, call myself a permanent resident and can differentiate a coyote from a lost dog at 50 paces. Because there was a considerable lag between my arrival and my residency card, I took the opportunity to speak at a few conferences this year: one on inclusive museums (http://onmuseums.com), Trent University’s Contesting Canada (https://www.trentu.ca/canadaconference2015/) and UBC’s Society for the History of Children and Youth conference (http://shcyhome.org/conference/). I also revisited some of the material in my thesis (including all the yummy stuff that didn’t make it) and published two articles. One article, in the Spring 2015 issue of Ontario History Journal, is about Ruth Home and the development of the Royal Ontario Museum’s educational programming (https://www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca/index.php/recent-oh) . I’m also publishing a piece on Kate Aitken and culinary education at the Canadian National Exhibition, to be featured in the next issue of CuiZine Journal (http://cuizine.mcgill.ca).

Last fall I successfully defended by doctoral thesis, got married and moved across the continent—all within a matter of weeks. I’m happy to report that America has been quite kind to me: I now have an intimate knowledge of the vagaries of the Los Angeles Metro system, call myself a permanent resident and can differentiate a coyote from a lost dog at 50 paces. Because there was a considerable lag between my arrival and my residency card, I took the opportunity to speak at a few conferences this year: one on inclusive museums (http://onmuseums.com), Trent University’s Contesting Canada (https://www.trentu.ca/canadaconference2015/) and UBC’s Society for the History of Children and Youth conference (http://shcyhome.org/conference/). I also revisited some of the material in my thesis (including all the yummy stuff that didn’t make it) and published two articles. One article, in the Spring 2015 issue of Ontario History Journal, is about Ruth Home and the development of the Royal Ontario Museum’s educational programming (https://www.ontariohistoricalsociety.ca/index.php/recent-oh) . I’m also publishing a piece on Kate Aitken and culinary education at the Canadian National Exhibition, to be featured in the next issue of CuiZine Journal (http://cuizine.mcgill.ca).

But now, it’s time to get back to the ‘real’ (non-academic) world. No more academic resume: re-format! I’m in the land of one page CVs, bullet points and brevity.

Full disclosure: I’m currently being interviewed at a few museums and hope to be employed as soon as the employment gods smile upon me. What follows are some nuggets of wisdom for those of you who are currently in the throes of looking for work in the museum field. It’s a highly competitive environment and waiting for someone to die so you can get hired doesn’t qualify as a job-hunting strategy. Here are some proactive points for you to bear in mind.

1. Think about your area of expertise more broadly.

I know you want to stay in your field. We all do. We are willing to juggle multiple part-time gigs just to keep it that way. It’s important, however, to consider how you may be limiting yourself by over-categorizing your expertise. We all do this—academia encourages us to identify and classify ourselves, and our research areas, very early on. When you’re looking for work these defining lines can actually do more harm than good. I consider myself to be a Canadian museum historian: not surprisingly, that’s not exactly in demand in Los Angeles. So now I’m a social historian. Period. Or a museum education historian. Or a museum educator who has researched the historical context of her profession. Or a history educator. Or a science educator. Or an arts educator. If you’ve have had the privilege of grad school bestowed upon you, you’ve also had the privilege of honing your research and writing skills over many, many years. Read: you can pick anything up. You may know everything about the BNA Act of 1867—which may have mattered at one point, but it may not matter now. Your new job may be about operating a spindle. Deal. You need to convince your potential employers that you are the best spindler around. And the truth is you are--because you are super committed, you like the way alpacas look and you have read everything about spindling on the Internet. Maybe you even bought a book about it—which you have yet to read, but having books is kind of like reading them isn’t it? (That last part is a joke—everything else isn’t).

2. Develop (and recognize) your skill set.

Know that your skills are more transferable than you think they are: getting a graduate degree makes you a great a) researcher b) communicator c) grant writer (for yourself) d) coordinator—you had to coordinate your entire life to be able to get a graduate degree! Focus on the skills that your time in academia helped you learn (time management, ability to self-direct, ability to pitch a project). Develop the ones that you know are in-demand, particularly techie skills. Build yourself a website. Start tweeting. I know, I wish there were more characters too, but in Twitterland, 40 is the new 300. It’s also a great way to connect with fellow history educators (plug: follow THEN-HiER-- @thenhier!)

3. Pay a visit.

3. Pay a visit.

To state the obvious, be sure to visit the museum before the interview. In order to narrow down your focus, think deeply about the kind of institution you want to work for, and then go check them out. What do they represent in terms of their institutional values? What was the visiting experience like for you? Is that mission statement embodied on the floor? As preparation for the interview, be sure to familiarize yourself with their website, what they offer in terms of programs and collections, and think about how you might ‘fit’ with them. This is also the time to network with people who work in institutions you have your eye on and connect with them over the phone or, better yet, in person. Online applications can only get you so far. The people you meet may have insight into future hires and can give you a sense of what it’s really like to work there.

4. Gather insider intelligence.

Volunteer where you think you might want to work. I know, you thought the days of being a volunteer were over—but truthfully, there is no better way to learn about institutions—with the added bonus of personal fulfillment. The stuff you pick up from being on the floor will serve as great fodder for discussion when you get interviewed, and you’ll get a sense of how things operate. If you don’t like what you see, you can still learn from it. Even if you ultimately decide that the actual lived reality of working in that institution isn’t for you, it hasn’t been a waste. You’ve donated your time to a great cause. Gather up those ideas and store those insights for later— they’ll be useful when you’re developing your own programs or exhibits and need to analyze what works (and what doesn’t) in museums.

5. Don’t apologize for your educational experience.

There were many times that I thought about erasing my PhD from my resume. It felt particularly twisted that a PhD in museum education was potentially keeping me from landing a museum education job. But I was told that it branded me as an academic, which could backfire when I applied for positions that only required a BA, and were not high on the pay scale. In the end I decided to honour my research, which happens to be completely relevant to my career. The solution: I put my academic qualifications on the second page of my CV, and led with my work experience on the first page instead. My CV does not scream ‘academic’—but my potential employer will also know that I have extensive educational experience and life experience that I bring with me to the floor. And personally, I want to work with someone who values that.

6. Don’t apply for something you don’t really really want.

We’ve all heard that finding a job is like the lottery—you have to play in order to win. Raise your odds, we’re told, and apply to as many places as possible, because it’s a numbers game. I recently met someone who told me that he applied to 150 universities before landing his teaching job. Yes, 1-5-0. I’m going to go out on a limb and contradict the numbers game philosophy. Applying for jobs is a full time job in and of itself. Each application, if you’re taking this seriously, is an act of attention. Pay attention to what the job description is actually saying. Craft your resume as a response. Each application is also an act of representation. You are tasked with representing your entire existence in a one-page cover letter and a max two page CV. Those three pieces of paper have to correlate with the position, they have to show people a glimpse of who you are, and they have to be torturously brief. A lot of job hunters erase the sparkle and personality from their CVs by mirroring job qualifications too closely, or opting for an over-used template because they are too focused on getting as many resumes as possible out into the universe. I think that one well crafted and thoughtful application is worth a dozen formulaic ones. When you’re trawling online job boards and reading through job descriptions, make sure you can see yourself in them. Before you apply, make sure you care about it. Bring that enthusiasm and authenticity to the page. You don’t have to be salivating about the thought of having to learn Raiser’s Edge, for example, but if you’re going for that job, you should have a sustained interest for fundraising. And you should be able to communicate that zeal honestly in your cover letter.

It’s more complicated than being “at the right place at the right time”—as those lucky enough to be employed in museums often quip. It’s about understanding what the right place is for you, and being proactive about what you want. Ultimately, the best way to find meaningful employment in a museum is to start in a job or within an institution that you really care deeply about already--and to which you’d love to contribute. Just like your cover letter says.

Photos:

Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo by Diana Lee, Creative Commons.

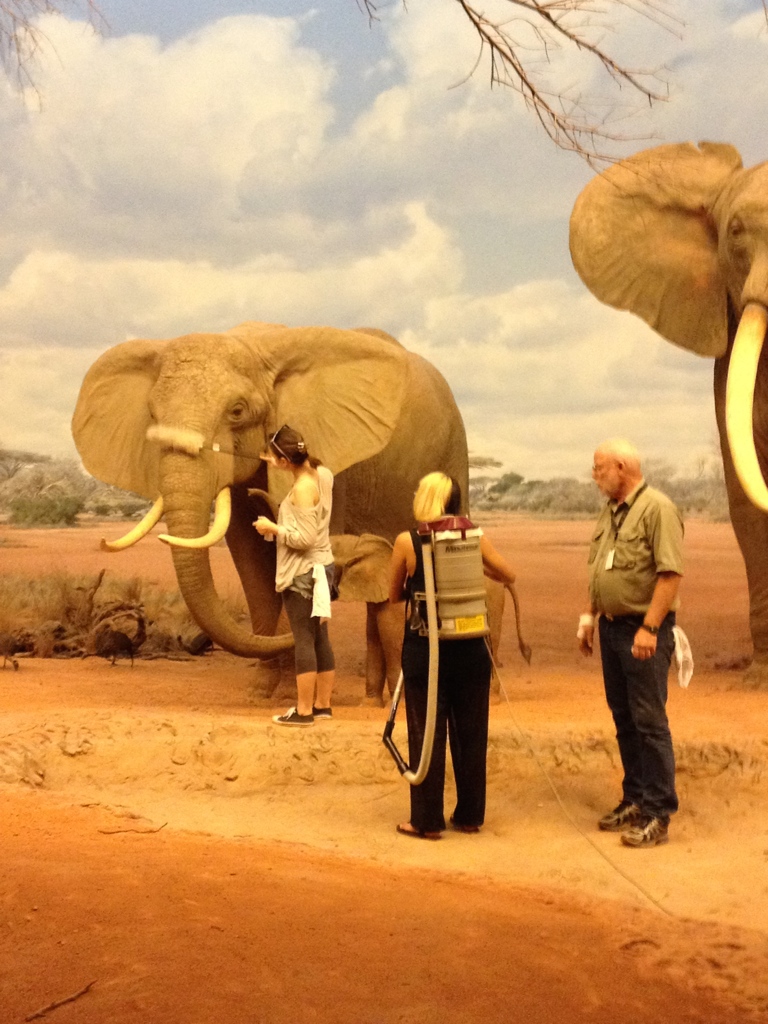

Natural History Museum. Photo by Kate Zankowicz.