OBJECTifying the Past: Using Objects to Talk about Past and Present

10 September 2012 - 3:26pm

Images can be objects, too.

This year, I invited undergraduate students in an introduction to Canadian History course to analyze some of the most iconic images of the twentieth century: posters from the First and Second World Wars. These images inundate popular culture and help form our own conceptions of the conflicts and of the century. Think of the pointing figure of Lord Kitchener demanding “Britons Want You,” or of Rosie the Riveter encouraging American women that “We Can Do It.”

Canadian War Museum, Artifact Number 1972008-007

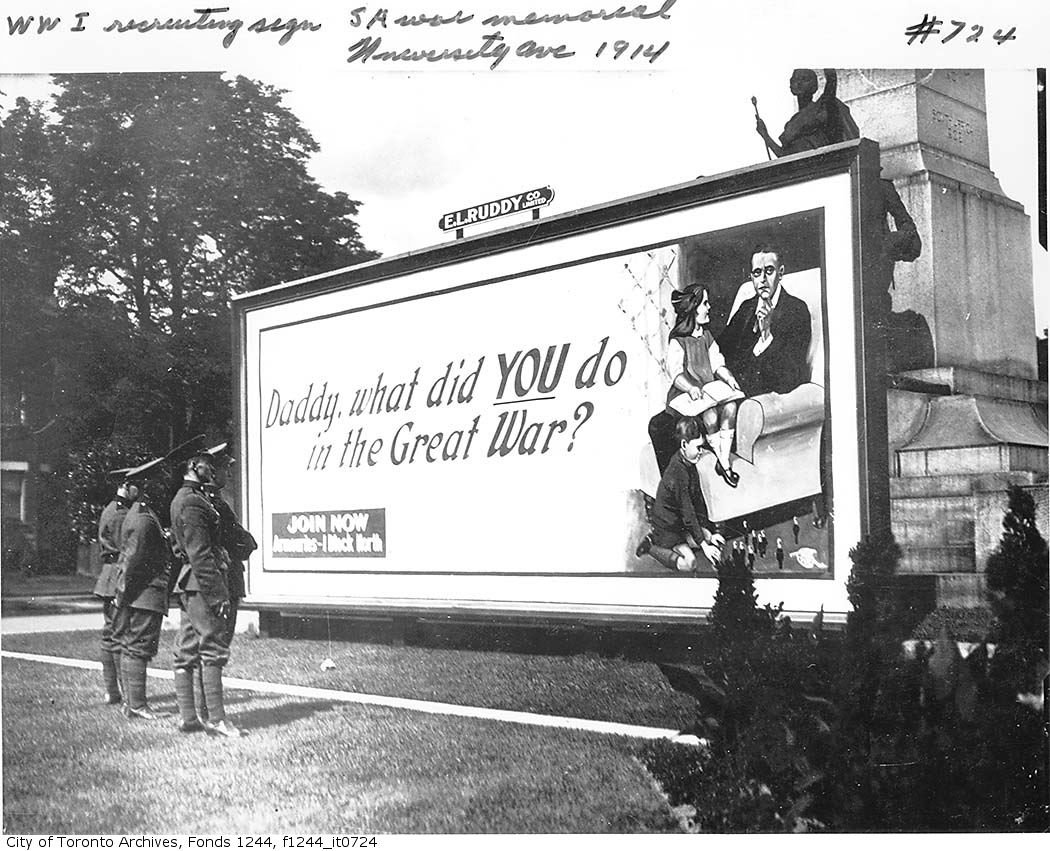

In a Canadian context, posters advertised the war to Canadians through slogans such as “The Empire Needs Money, Men, and Munitions: Which are you Supplying?” and “Lick Them Over There, Canada!” Often, Canadian posters were modeled after those used in Britain. Sometimes imagery and wording was adapted to appeal to Canadians, sometimes the same poster was used in Canada as in Britain, and some posters were developed specifically for use in Canada. Understanding that the images used in war posters often had roots elsewhere, most usually across the pond, helps us fit war and its promotion into a global rather than only national war effort. For example, a Great War poster with the slogan “Daddy what did you do in the Great War?” was used both in Britain and in Canada. A photograph from the City of Toronto Archives shows images from this poster used on a recruitment billboard at the South African War Memorial at University Avenue and Queen Street West in Toronto around 1914.

City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 724

The imagery in war posters present some interesting questions. How is the war being described? Are these children shaming their father into action? What kind of “appropriate” actions might he take? How might images such as this fit within a growing shortage of volunteers by 1915, and an increasing momentum towards Conscription by 1916?

We have to remember that war posters as objects in their original contexts were displayed and interacted with on a daily basis. In this sense, bringing an object into the classroom either physically or through the use of assignments based on primary sources challenges students to examine not only the information presented by the object itself, but also how the object might have been used or encountered. This includes exploring the “thingness” of the thing (or an innate state of being) together with its uses and the environments that might have surrounded it both in the present and in the past. War posters now sit in dark storage rooms and live online in digitized collections. War posters then sat at the bottom of war memorials, lined city streets, and covered billboards.

Objects present opportunities to discuss continuity and change. Asking how an object might have been understood in the past then begs the question of how they are understood now. The poster above, created before the Conscription Crisis of 1916-1917, can be analyzed both within the environment that produced it in 1914 and within the events the proceeded it (such as Conscription).

Objects, then, serve to both connect past and present but also to challenge assumptions that the past was as we understand it today. If we in a classroom can “read” a poster in a specific way, we must also ask ourselves how the same image when contextualized within another era might present ideas or messages alternate to the ones we read into them today.

Below are some helpful links to more posters.

How do you frame your discussions and interpretations of posters in your classroom?

Canadian War Museum Poster Collection

Imperial War Poster Collection (UK)