Misconceptions of teaching history in a B.Ed program

14 September 2015 - 1:32pm

Misconceptions of teaching history in a B.Ed program

Linking this blog to our monthly theme of something I learned over the summer that changed my understanding of history, I have been thinking more and more about a question a colleague asked me regarding the misconceptions that surround teaching history. Due to the recent changes in Ontario, B.Ed programs are now two years and all faculties of education have had to make alterations to their B.Ed programs. A colleague of mine who is teaching the first part of the B.Ed history course to incoming B.Ed students wanted me to give her a brief overview of the main misconceptions teacher candidates have towards teaching history. This got me thinking about how future history teachers believe history should be taught to their future students.

My first suggestion was to get teacher candidates to think of history as more than an act of transmission, moving away from a “broadcast” approach of long lectures followed by textbook readings and questions. Darling-Hammond and Baratz-Snowden (2007) state that teacher candidates “often believe that teaching is merely transmitting information and enthusiastically encouraging students, rather than assessing student learning to guide purposefully organized learning experiences with carefully staged supports” (Darling-Hammond & Baratz-Snowden, 2007, p. 117). Getting students to think critically about historical people, events and incorporating non-dominant narratives is crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of historical knowledge. I also suggested Peter Seixas’ (2002) “The Purposes of Teaching Canadian History” as a first day reading that might spark some discussion amongst teacher candidates and get them thinking more about the importance of historical consciousness and challenging historical myths in their classrooms.

My first suggestion was to get teacher candidates to think of history as more than an act of transmission, moving away from a “broadcast” approach of long lectures followed by textbook readings and questions. Darling-Hammond and Baratz-Snowden (2007) state that teacher candidates “often believe that teaching is merely transmitting information and enthusiastically encouraging students, rather than assessing student learning to guide purposefully organized learning experiences with carefully staged supports” (Darling-Hammond & Baratz-Snowden, 2007, p. 117). Getting students to think critically about historical people, events and incorporating non-dominant narratives is crucial for gaining a deeper understanding of historical knowledge. I also suggested Peter Seixas’ (2002) “The Purposes of Teaching Canadian History” as a first day reading that might spark some discussion amongst teacher candidates and get them thinking more about the importance of historical consciousness and challenging historical myths in their classrooms.

I also mentioned that the incorporation of historical thinking concepts (HTCs) in the new Ontario curriculum will assist teachers to think more about the purpose of their lessons and how to critically examine past events using primary sources. Having teachers include more online sources and technology into their lessons will hopefully ease the transition away from an over reliance on the course textbook and to a more disciplinary approach to teaching history. As Sandwell and von Heyking (2014) point out in the introduction to Becoming a History Teacher, teachers who are getting students to “do history” are discovering that “students experience, and come to know historical thinking: the complicated, nuanced process of evaluating the meanings and significance of often-conflicting evidence” (Sandwell and von Heyking, 2014, p. 3). The challenge in getting teacher candidates to embrace a different approach to teaching history is to start in B.Ed courses but to also follow up this “introduction” with meaningful and ongoing professional development throughout their teaching careers.

I also mentioned that the incorporation of historical thinking concepts (HTCs) in the new Ontario curriculum will assist teachers to think more about the purpose of their lessons and how to critically examine past events using primary sources. Having teachers include more online sources and technology into their lessons will hopefully ease the transition away from an over reliance on the course textbook and to a more disciplinary approach to teaching history. As Sandwell and von Heyking (2014) point out in the introduction to Becoming a History Teacher, teachers who are getting students to “do history” are discovering that “students experience, and come to know historical thinking: the complicated, nuanced process of evaluating the meanings and significance of often-conflicting evidence” (Sandwell and von Heyking, 2014, p. 3). The challenge in getting teacher candidates to embrace a different approach to teaching history is to start in B.Ed courses but to also follow up this “introduction” with meaningful and ongoing professional development throughout their teaching careers.

References

Darling-Hammond, L., & Baratz-Snowden, J. (2007). A good teacher in every classroom: Preparing the highly qualified teachers our children deserve. Educational Horizons, 85 (2), 111-132.

Peter Seixas. (2002). The Purposes of Teaching Canadian History, Canadian Social Studies, 36(2).

Sandwell, R., & von Heyking, A. (Eds.). (2014). Becoming a History Teacher: Sustaining Practices in Historical Thinking and Knowing. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Photos:

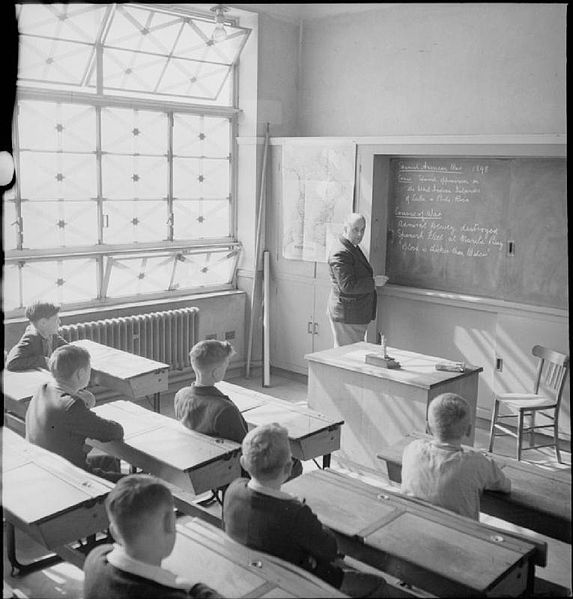

1. "Young Britons Study American History Education in Wartime" from Wikicommons.

2. Photo by author.

Misconceptions of teaching history to BEds

Two approaches I try to use deal woith reflective peices based on practicum experiences since there is too often a disconnect between what we do in teacher education and what is done in the field. I have a chapter in Becoming a History Teacher that examones some of this work. The other approach challenges student teachers through the use of "dsicrepant events" involving both primary and secondary sources. It is interesting when two accounts of an event differ so much from textbook to textbook— a phenomenon usually expected in primary sources. From here we look at events and sources of interpretation and rank the "reliability" of the source.

Two challenges in translating this work to the field, even in Ontario, are the variations in understanidng of disciplinary thinking by school mentors and the tyranny of content coverage which still exists.

In my visits to schools I have noticed progress in reconceptualizing the nature of history as a discipline in schools. Given a generation of work we can continue in this direction.

A bump in the road may come as pundits and others fret about the lack of historical knowledge—facts— we possess. In these cases we had best have useful responses or we return to thoughtless transmission teaching.