The Integration of Multiple Perspectives in Secondary History and Social Studies

8 April 2013 - 12:52pm

Integrating multiple perspectives into history and social studies education presents a range of challenges for teachers and students. Perspectives are complex and perspective communities, particularly when we speak about national, religious, cultural, ethnic, or linguistic groups, are diverse and multi-faceted. Perspectives are tied to ways of knowing and living in the world. They are ideological, and gendered, and they are socio-economically, geographically, and temporally situated. Perspectives have a past, present, and future, and these intersect and overlap in a multiplicity of ways with the interests and perspectives of other perspective communities.

Integrating multiple perspectives into history and social studies education presents a range of challenges for teachers and students. Perspectives are complex and perspective communities, particularly when we speak about national, religious, cultural, ethnic, or linguistic groups, are diverse and multi-faceted. Perspectives are tied to ways of knowing and living in the world. They are ideological, and gendered, and they are socio-economically, geographically, and temporally situated. Perspectives have a past, present, and future, and these intersect and overlap in a multiplicity of ways with the interests and perspectives of other perspective communities.

Taking on a perspective that is not your own becomes more than speaking with critical attention about members of that perspective community, because it means making the move from speaking for or about to speaking from another’s standpoint. This inevitably provokes fears that whatever is articulated through another perspective would be ‘unjust’, ‘inauthentic’ or ‘untruthful’. Such situations are encounters with liberal guilt and enlightenment scientism, and these reactions are deeply embedded in contemporary middle-class Canadian perspectives. The tendency to extend these into other perspectives both reveals and conceals the deep entrenchment of particular sentiments and expectations within a perspective community. To the extent to which we as teachers come to be aware of the complexity and impediments involved in perspective taking, we can help our students and ourselves to confront the challenges of understanding how members of other perspective communities understand and live in the world now and in the past.

The conversations around multiple perspectives have been with us for a long time in the history and social studies education world. In Alberta, about a decade ago, we transited some difficult perspective-taking territory to become one of the few jurisdictions at the time to name the perspective domains through which teachers would share the curriculum with students. Complementing a western, liberal, Anglophone, middle-class, perspective community standpoint, teachers are required to integrate Francophone and Aboriginal perspectives into teaching and learning. Eight years after the program rollout we are still struggling to find ways to better integrate perspectives from these ‘other’, non-dominant communities into classrooms. While we do not have a lot of research yet to say what is happening in classrooms in terms of multiple perspective integration, anecdotally, we know that efforts to integrate these perspectives tend to occur when teachers perceive that program outcomes are tied to a particular perspective community. For example, integration of Aboriginal perspectives occurs when residential schools and/or treaties are discussed, but not necessarily when globalization or the Renaissance is the topic. Francophone perspectives might be integrated when the topic is minority language rights or federalism, but not when the topic is Japan, or the Cold War.

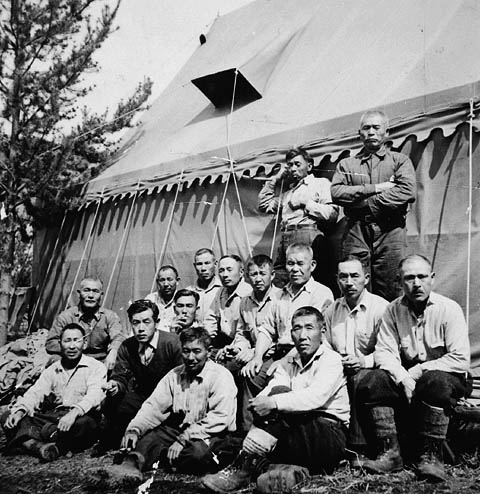

As a teacher educator I have been giving increasing attention to the integration of perspective taking in history and social studies. In courses I have taught in this academic year a colleague of mine and I have been conducting a study tied to an assignment which asks students to produce an ‘Animoto’ video which offers some element of Alberta social studies content through an Aboriginal or Francophone perspective. (A couple of students tried Métis perspectives, too.) The challenge was to look at program outcomes not necessarily associated with the perspective community the students were working with and offer another narrative that emerges out of that ‘other’ perspective. Interestingly, students took on Aboriginal perspectives far more often than Francophone perspectives, and they preferred to work with historical material rather than content tied to understanding ideology, civics, economics, or other social science content. As expected, many students chose to tell stories associated with Aboriginal people through Aboriginal perspectives, capturing what they could of the narrative styles they associated with Aboriginal storytelling. One that I found curiously successful was a story about the internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War told from an Aboriginal perspective. The images associated with the seizing of land and the relocation of people based on racialized identification was a familiar narrative. It was the potential of interchangeability of the images in relation to the story that was remarkable.

Yet, a key challenge in evaluating these videos is the extent to which each video was successful in conveying a non-dominant perspective. How will we know whether we have managed to produce a perspective that is not our own? This is the authenticity moment that is difficult to resolve and it may be irresolvable. Who is entitled to judge? Unfortunately, such problems function as convenient impediments to non-dominant perspective integration. Teachers can invoke a non-entitlement to judge because they lack membership in a community associated with another perspective. These are often complemented with the absence from the classroom of members associated with the non-dominant perspective communities, what Dr. Dwayne Donald calls a disqualification argument. I believe in the interests of a better understanding of Canada as a national community. In the interests of better understanding how dominant perspectives function, we need to push past our fears and overcome our resistance to trying by recognizing how the dominant perspective delimits the conditions for exploration and insight.

How do you, as an educator, endeavor to speak from another perspective? What sort of challenges have you faced in producing a perspective that is not necessarily your own?

Photo: Group of interned Japanese-Canadian men at a road camp on the Yellowhead Pass, March 1942. Original held at Library and Archives Canada. Copyright expired.