Diary of a History TA: Why This Semester is Working

16 November 2013 - 2:26pm

Something happened to me earlier this semester that doesn’t happen often after teaching a tutorial. I was climbing the stairs from the second floor to the sixth, and wandering around the halls covered in posters of faces of famous writers, anthropologists, and political scientists. Each poster featured quotations from some brilliant-but-now-cliche thing running across profile photos in hideous 90s fonts (thank you English Department for not changing your hallway decor), and I was smiling.

Something happened to me earlier this semester that doesn’t happen often after teaching a tutorial. I was climbing the stairs from the second floor to the sixth, and wandering around the halls covered in posters of faces of famous writers, anthropologists, and political scientists. Each poster featured quotations from some brilliant-but-now-cliche thing running across profile photos in hideous 90s fonts (thank you English Department for not changing your hallway decor), and I was smiling.

I don’t think it is my diet - that hasn’t changed much. I’m not working out more, or less for that matter, so my body likely doesn’t have a significantly different amount of energy one way or the other. Perhaps I’m working more intently on my thesis than ever before (I’m doing my best to not be lazy), but I don’t know if there is a connection there. I’m sleeping less, never sleeping in, and, by the end of the semester, may have financial concerns arising from my low rate of pay. So, ultimately, I don’t really think that it is anything that I have done which is making me smile at the end of tutorials (even my 8:30 am tutorial!). I may even have reason not to smile.

So I’m assuming it is something my students are doing.

They are participating at a rate that I have never seen in any of the other classes with whom I have worked. Yes, even at 8:30 in the morning. And they are attending, asking questions and answering questions with each other. They agree with each other and disagree with each other, and move discussion along among themselves really well. I help out when needed, but this isn’t as frequent as I would have expected. I have no idea why.

Kind of. (This wouldn’t be a useful posting if I didn’t have some kind of rational explanation).

This semester I am assisting for my first ever thematic course. This is in direct contrast with the regional courses that I have worked with in the past, because the students are focusing entirely on a theme and how that theme has changed over time in the monolithic “Western world.” And in this class the theme is gender. You couldn’t possibly ask for a more pertinent theme for the post-1990s generation to be discussing. Particularly this semester (thank you Robin Thicke, Miley Cyrus and extensive media coverage).

The thematic focus allows the students to engage with the material without feeling quite so constrained by the need to be historical. Not that they aren’t being historical, but because they enter the class with a sense (an overly generalized sense) of what ‘society’ thinks of sexuality today. They can contrast this quite easily with discussions of what sexuality looked like in Victorian England or in the early industrial period in New England, or in Ancient Greece. And they contrast this really quite well.

So they are very good at presenting their generalized, early twenty-first century Canadian sense of sexuality as the product of all of this history. It is almost logical - a great story of progress (much to my dismay). The history is simple because it is only concerned with one issue. I think this matters. This is in contrast with the whole collection of issues that are encountered in a standard regional history course. To be clear, this course is not simple - far from it - but the task of understanding the past through the lens of gender makes studying the past somewhat less intimidating than studying the past through the lens of gender and race and class and colonialism and power and governance and so on. And, best of all, they are still discussing these other historical issues as they pop up, but only as they are related to gender - they have become approachable and not confusing. This is good training for their burgeoning historian minds, seeing as historians use frameworks with the same goal of simplifying the past into something that can be “knowable” (apply whatever postmodern, modern, or pre-modern definitions you have to this term, I think they all apply).

It also means that I get to teach against a narrative which places the present as the logical and obvious development of the past. This is what they all think more often than not. They start their analysis by criticizing the past for being filled with so many foolish people that clearly didn’t know any better to think differently and treat people better. If you remember a post from last year where I was teaching a Modern Chinese History to a class that was filled with students from mainland China, then you would think this wasn’t a blessing in disguise. But it is - because these students haven’t been told about the foolishness of past notions of sexuality in a dogmatic way. Rather I suspect they have learned it from the media or off-hand comments about sexual history in their high schools - accidental knowledge, not forced information. This information was tangential to lessons rather than the central feature of the curriculum.

And, this semester, the students have so far been very good at getting a better sense of what makes looking at the past so troubling and difficult for historians; the need to be empathetic with the past and attempt to understand it according to its own terms. That is a tough lesson. Particularly when you believe in a progress narrative. But the students are starting to get it, with some wanting to hold onto philosophies that say the present is better than the past, and others really working to undermine this narrative that they have learned. It is exciting to watch it happen week-after-week and class-after-class.

But I’m also doing something that forces me to step back from the classroom and give students a greater ownership over how each lesson develops. The first twenty minutes I do not talk. At all. I don’t give them questions, or suggestions, or ideas, or frameworks, or context, or banter about the lecture, or anything. Aside from breaking students up into small groups, and listening to what they are saying to make sure they are on task, and maybe jumping in with a suggestion if (somehow) the conversation dies down, I sit in the classroom and quietly wait till the timer runs out. And the discussions are, largely, quite impressive - the students are working hard to challenge their assumptions when looking at the primary documents - the 1920s was particularly shocking to them - and they are attempting to challenge their knowledge about the past frequently. On their own. It is incredible to watch because I’m quite certain that I wasn’t working like that when I was in my first year (actually, I can vividly remember one episode from when I was in a senior-level seminar on the Enlightenment where I failed to do so entirely).

After only a few weeks of indoctrinating them into the idea of understanding the past according to its own terms, my students are actively struggling with it. And I think this is because I pointed out their prior ahistorical judgements, and because they are doing most of the learning on their own. It is all because I talk less and they talk more and my job is, simply, to offer them assistance when they are going astray (and only if somebody else can’t help them out first).

I think this is why I leave tutorials smiling.

What are your strategies for TAing a thematically based history course?

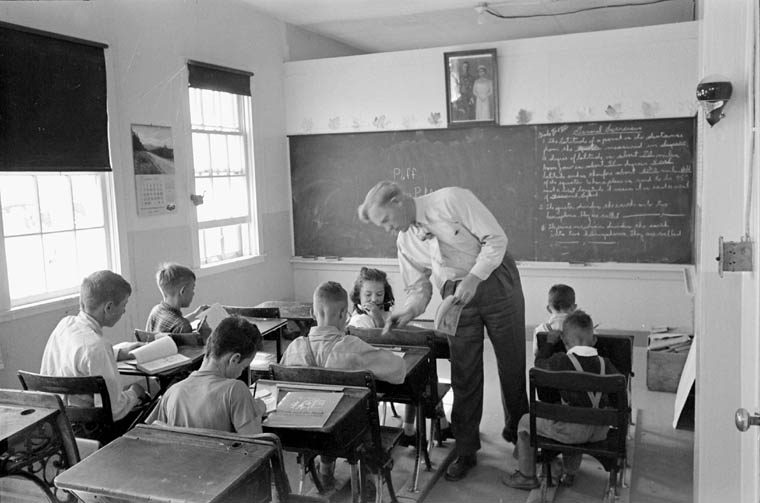

Photo: Photo:Classroom of Laidley Spring School on the Matador Co-operative farm about 40 miles north of Swift Current, Sask. Teacher is R. L. Moen. Credit: Gar Lunney/National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque/Library and Archives Canada/PA-159647. Copyright: Expired