Diary of a History TA: Challenging Students' Assumptions about the Past

12 March 2013 - 7:55am

My seminars have presented me with an odd challenge this semester. I am teaching a course in which I have very little background. I am teaching students who have already learned about all of the content before. I am teaching students who are nearly entirely from another country. And I’m teaching students who are dedicated to their reading and their work and their learning. I suppose this is what happens when you are teaching the history of China from 1800 in a city like Greater Vancouver (where, I was recently informed, the dominant conversational language is now Mandarin).

My seminars have presented me with an odd challenge this semester. I am teaching a course in which I have very little background. I am teaching students who have already learned about all of the content before. I am teaching students who are nearly entirely from another country. And I’m teaching students who are dedicated to their reading and their work and their learning. I suppose this is what happens when you are teaching the history of China from 1800 in a city like Greater Vancouver (where, I was recently informed, the dominant conversational language is now Mandarin).

I have four students in my class whose last names are likely of European origin. Two of those four have told me that they are from Europe. The rest, as my professor exclaims with delight, have “Chinese” names. Nearly all of them are from the People’s Republic of China, were raised underneath their curriculum, and have learned a great deal about their country’s history since 1800. They have learned it in a language that they are comfortable with, speak daily, and that reinforces the Chinese Communist-Nationalist narrative. As such, their assumptions about the Chinese past, and the words that they use to describe it, are uniformly condemning of China’s pre-Communist past. Above all else, their existing knowledge is the greatest challenge that I encounter week after week.

The professor for whom I am working has structured the class in such a way that we can challenge the students’ assumptions about the past. Each week the students write a short reading response to some primary or secondary source (other than the textbook) that they have been instructed to read. These responses are quickly assessed and evaluated and promptly returned to students (or, at least, this has been the case thus far). Often the students are quite surprised when they don’t do as well as they think they should, and every week I have the same chat with the class. “Analyze, don’t summarize. Thesis and ideas matter. And,” more importantly, I tell myself, “make sure you are looking at your assumptions about China’s past – all of the one’s you have been told while growing up. Is there evidence for them?”

One week we read a work by Lu Xun entitled Kong Yiji. Lu Xun was an author that popped up out of the May Fourth Movement and is widely regarded as the best Asian short story author of the twentieth century (and, based on the few stories I have read, I can only possibly highly recommend him). He used satire and metaphor masterfully to critique Chinese society in the early twentieth century while also critiquing the direction in which he felt the country was moving. He is well-known in China for being critical of everything, including modernization (which many in the May Fourth Movement embraced much less guardedly). Almost all of my students (forty-five minus four) had read this story before. They told me this in tutorial and, without them knowing it, they told me in their reading responses. The words they used to describe the character of Kong Yiji and the people that harassed him were the exact same; outdated and old-fashioned for the former, and cold, numb, and heartless for the latter. In over twenty responses. The exact same words.

I should have mentioned earlier in this post that my professor is excited about having so many knowledgeable students because it gives us, as seminar instructors, an opportunity to worry less about content and more about developing historical empathy. It was clear to me after reading these responses that I was dealing with historical regurgitation, from a modern Chinese Marxist textbook in Guongdong Province into my classroom, translated as precisely as possible to the English. Certainly my job was far from complete.

The next week, as I was handing back the responses I saw many shocked faces at the grades that students received, I told my students that I caught them. I now knew their game of translation and their use of this course as a way of getting their humanities credit. But I was sure to couch it in friendlier language. It went something like this (though it may have been less eloquent): “Few people from China have the opportunity to study Chinese history outside of their country. Few people have the opportunity to challenge the ideas of the past that they have been taught by their government and the people that write their high school textbooks. But it is exciting – the single thing that I am challenged to do every single day of my professional career. And it has the potential to be transformative. Please don’t waste this opportunity – engage with the assumptions that you have about the past and challenge them and you will find the story of you country’s past far more interesting because of it.”

My challenges with this semester’s group of students are broad, and I suspect that I will write about them in more detail in the coming months. But the challenge of dealing with pre-requisite knowledge is perhaps as daunting as dealing with complete ignorance.

How do you deal with either one as an educator?

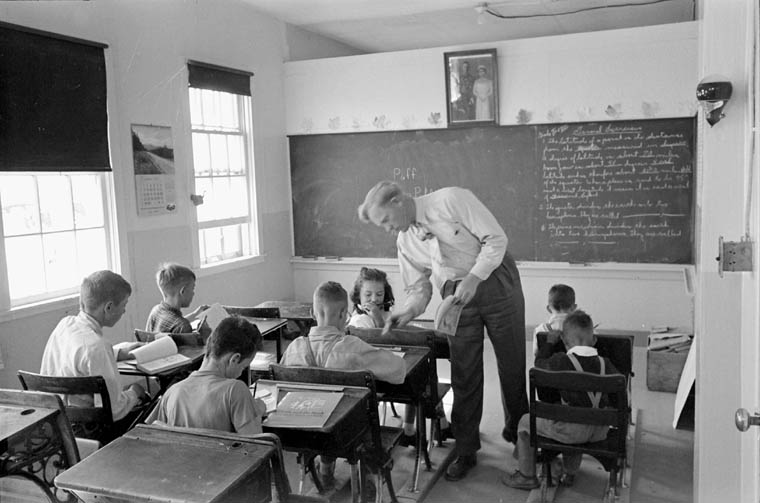

Photo:Classroom of Laidley Spring School on the Matador Co-operative farm about 40 miles north of Swift Current, Sask. Teacher is R. L. Moen. Credit: Gar Lunney/National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque/Library and Archives Canada/PA-159647. Copyright: Expired