British Columbia’s Contact Zone Classrooms, 1849–1925

12 June 2015 - 1:05pm

N.B. This blog originally appeared on activehistory.ca

By Sean Carleton

Canada’s sordid history of colonial education has yet again become a topic of controversy and debate. While the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is coming to an end, new layers are still being added to Canada’s history of colonial schooling, including the horrific findings of abuse and torture and nutritional experiments in residential schools. The overall picture, of course, is disturbing. This is why many historians were confused and dismayed by Ken Coates’ recent suggestion that now is the time to move beyond this difficult past. In response, Crystal Fraser and Ian Mosby rightly reject such an assertion and argue that there is still much to learn about the complexities of colonialism and schooling in Canada, past and present.

My own research confirms this position, and, though I am still writing my PhD dissertation, I wanted to contribute to this important dialogue. Inspired by recent words of encouragement from award-winning filmmakers Alanis Obomsawin and Peter Raymont about the importance of history, activism, and film, I decided to make a short film to share part of my research that supports calls for the need to continue to critically examine Canada’s history of colonial schooling.

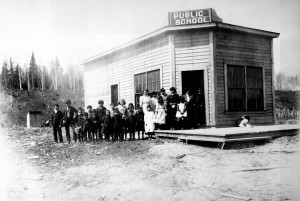

Generally, my dissertation looks at the relationship between social formation, settler colonialism, and the rise of state schooling in what is now known as British Columbia between 1849 and 1925. As such, my research does not examine residential schooling and public schooling as entirely separate forces. Instead, I show how colonial, provincial, and federal governments used various forms of education – including mission, day, residential, and even public schools – as part of the project of dispossessing Indigenous peoples from their lands and training Indigenous and non-Indigenous children to eventually take up their respective (and profoundly unequal) roles in an emerging settler society. My work thus argues that state schooling, overall, is an essential component of settler colonialism.

One of the interesting findings from the juxtaposition of different schooling histories is that Indigenous children often attended colonial common and provincial public schools in British Columbia. Historian Jean Barman has previously identified this practice; however, she claims that it was sporadic and that it stopped by the early 20th century when the federal government and different missionary bodies established new boarding and industrial schools for Indigenous children.[1] In contrast, my research, which builds on Barman’s excellent work, shows that in many parts of the province the practice of Indigenous children attending public schools continued well into the twentieth century.

The following film briefly explains this part of my research and shows that British Columbia’s public school classrooms were complicated spaces that can be understood using Mary Louis Pratt’s concept of “contact zones.”[2] This finding is significant because it demonstrates that public schooling was complicit in the colonial project and thus confirms that there is still much to learn about Canada’s complex history of colonial education.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9OBIdbDy14w#action=share

Sean Carleton is a PhD Candidate in the Frost Centre for Canadian Studies & Indigenous Studies at Trent University. He is completing a dissertation on the history of colonialism, capitalism, and education in Canada.

Photo:

Indigenous and settler children outside a public school in Prince George, Lheidli T’enneh Territory, BC, 1911.

Royal BC Museum, BC Archives

Notes:

[1] Jean Barman, “Schooled for Inequality: The Education of British Columbia Aboriginal Children” in Children, Teachers, and Schools in the History of British Columbia edited by Jean Barman, Neil Sutherland, and J. Donald Wilson (Calgary: Detselig, 1995), 57-80.

[2] Mary Louise Pratt, “The Arts of the Contact Zone” Profession 91 (1991): 33-40.