Using Identity, Family History and Family Artifacts to Connect with the Past

5 December 2013 - 11:02am

History educators often encounter learners who are not as passionate about the past as they are. In mandatory history courses this is a perpetual challenge.

History educators often encounter learners who are not as passionate about the past as they are. In mandatory history courses this is a perpetual challenge.

There are dozens of reasons to learn history, as most who regularly read this blog would surely agree. If there is one reason that may receive broad support it is to foster an ongoing relationship to the past in the people with whom we work – students, visitors, and other audiences. To make the past meaningful; to make it a place we are curious to visit, and to revisit (so-to-speak); to explain the present; to imagine a different future; and, to know who we are in the flow of time, in our ecologies, and in relations with others. These are some potential outcomes of participating in individual and collective practices of historical consciousness.

How can educators foster individual interests in the past? How can educators nurture student motivation to go on learning about the past - after student coursework is completed, or after the visitor leaves the museum? What are some personal prompts, or ‘hooks’, that can be useful to building an enduring and evolving connection to the past? Turning to identity and family may often provide opportunities to build bridges to the past and to those contexts for history and memory that may initially appear irrelevant, especially to more reluctant visitors. How are educators using identity and family history, memory and artifacts in class?

A not-so-successful example: In an undergraduate history methods course I took, students were required to write a final assignment about the details of the year of their birth. I say ‘details’ because the professor created a long list – perhaps 30 items – of information students were required to incorporate into an (inevitably awkward) essay about that year. The rules about incorporating this information meant that a range of sources had to be consulted, pushing students into different ways of finding obscure answers (such as using that old technology microfilm!). If any of the listed details were missing, marks were deducted accordingly. The value of the paper was assessed on its commitment to thoroughly representing facts about the year of our birth, according to the professor’s criteria, rather than student-driven interests or questions. In some sense the assignment was intended to make historical research personal, and the resulting essay felt like something that might produce a little nostalgia in my parents. But it was not necessarily an exercise that would keep me digging into the past, in my own future. I did finish my history degree nonetheless!

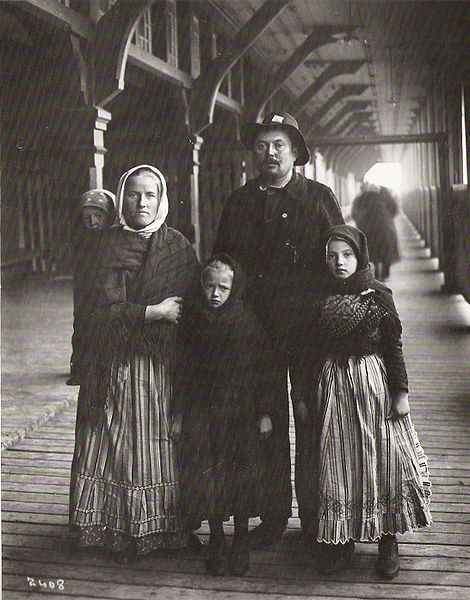

A more successful example: In contrast to the experience above was an assignment I received from Dr. Peter Seixas as I prepared to attend the Historical Thinking Summer Institute several years ago. Those of you who have attended Dr. Seixas’ workshops may have had the same assignment: bring an artifact (or photo/document) that is at least a decade old and that means something to you. Discuss how it makes you feel closer to, or farther away from, the past. Of course there is enough flexibility in this assignment that participants may not bring something that relates to their family, but from my observations the items chosen usually did illuminate both identity and family. I was visiting my parents when I received the assignment instructions, so I began looking through family archives of photos and documents. I found a photo that I didn’t remember seeing before, a photo that hadn’t registered much meaning before, but which, at that moment, became something that brought me closer to my past. The photo raised questions for me about how my grandfather’s life and his characteristics were echoing through time in my own curiosity about history, culture and social change. Since uncovering that photo and sharing it in the Institute workshop I have gone on to invest time in further investigating my grandfather’s life, including visiting archives, talking to family members, and reading about the social context of his work.

Giving students opportunities to interpret their own past(s), or how their identity and family has been shaped through time and given significance to their lives, can be a powerful platform for learning about the past. Such a bridge may help withstand the times when the past appears remote or irrelevant. It can stimulate a curiosity and motivation for students to explore farther afield than coursework or a museum visit may allow. It may not always be easy; tough questions and difficult stories can arise. Nevertheless, engaging with family history shows students that their own questions about the past are important, and that a passion for the past is something worth sharing with others.

What strategies do you use to connect students to family and identity when learning about the past? What works well, and what are some challenges?

Photo: German Immigrants, Quebec City, 1911. Found in NLA, PA-010254, copyright expired, Wikipedia Commons

- Se connecter ou créer un compte pour soumettre des commentaires