History on Film

5 February 2015 - 11:57am

The use of historical feature films in history classrooms emerged as a topic of debate in the 1980s, as technological advances, such as the VCR, made these films increasingly accessible. Those in favor of using historical films have pointed to the ability of movies to immerse us in the past, and have argued that historical films provide students an opportunity to develop their historical understanding, to gain increased historical empathy, and to connect the present to the past (Marcus & Stoddard, 2007; Marcus, 2005; Rosenstone, 1988).

The use of historical feature films in history classrooms emerged as a topic of debate in the 1980s, as technological advances, such as the VCR, made these films increasingly accessible. Those in favor of using historical films have pointed to the ability of movies to immerse us in the past, and have argued that historical films provide students an opportunity to develop their historical understanding, to gain increased historical empathy, and to connect the present to the past (Marcus & Stoddard, 2007; Marcus, 2005; Rosenstone, 1988).

Those who are hesitant to use historical films as teaching tools focus upon two “flaws” which, in their opinion, make the use of historical film unadvisable. First, some historians, such as Herlihy (1988), have argued that movies veer too far from standards of historical scholarship. By drawing the audience in and creating a false sense of reality, films lead their viewers to forget that much of what is depicted is conjecture, created by a director who has no choice but to fill in many of the blanks that exist within the historical record. As a result, the audience is not aware when a film departs from the “facts” and this can lead spectators to be easily misled. Second, these critics also claim that historical films do not lend themselves to the sort of analysis and debate that is characteristic of written, scholarly history (Herlihy, 1988; Jarvie, 1978).

Many historians and teachers have responded to Herlihy’s (1988) and Jarvie’s (1978) criticisms of historical films. These responses have tended to take one of two forms.

First, historians, such as Raack (1983), Rosenstone (1988) and White (1988) have challenged the claim that written history is somehow more accurate than history on film. According to White (1988) all accounts of the past are reproductions and even the most detailed micro-history will contain distortions. As a result, White challenges those who see the historical method as pure and objective, claiming instead that the shape of any historical text depends upon the concepts used by the historian as he/she transforms events into historical “facts” and patterns.

Second, some researchers have begun to address Herlihy and Jarvie’s implicit depiction of audiences as largely passive and easily misled (Marcus & Stoddard, 2007; Walker, 2006; Marcus 2005; Weinstein, 2001). Unfortunately, while this is a growing area of research, it is still under-developed and many of the studies that do exist are contradictory, with some researchers finding that students do approach films critically (Weinstein, 2001) while others claim that they do not (Marcus, 2005).

My own experience as a classroom teacher indicates that students can easily be led to adopt a critical attitude to films. But, naïve conceptions of what history is lead many students to apply their critical thinking skills in limited ways.

What leads me to think this? Well, for many years I have included a “history on film” assignment in my history courses. In its original form this task required students “to view and analyze the accuracy of a film related to the course content.” When given this simple prompt students quickly became “fact detectives.” They engaged in detailed fact checking, verifying every date, every statistic, and every minor detail. While I was happy to see that my students were questioning the accuracy of the films, I wished that they would focus on more than just the small details. Over the years I urged my students “not lose the forest for the trees”, or to “think about the overall narrative.” This message, however, seemed to get through to only half of my classes.

Eventually, after many, many students had gone through my history on film project, I began to realize that my pupils were running up against two different issues. Some were struggling because they still held a naïve view of history, conceiving of it as an objective copy of the past. Others had moved beyond this view of history, but lacked the historiographical background to think critically about the larger narrative(s) presented in a film.

This realization led me to redesign my project. Instead of asking students to watch a single film, students are now asked to watch multiple films, or to watch a film and then work with other materials. In either case students are presented with multiple narratives about an era or event, and thereby forced to confront the fact that history is made up of histories, that history is not a copy of the past, and that history is about interpretation. While this change to the assignment does not always lead to success, it has greatly enhanced the quality of the papers my students produce.

The pedagogical power of this small change raises the question, however, of what else can be done to further assist students to develop a critical appreciation of historical films.

What are your experiences using history on film? How do you make use of them? What problems have you encountered? Have you found any solutions?

Works Cited:

Jarvie, I.C. (1978). Seeing through movies. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 8, 378-397.

Marcus, A.S., & Stoddard, J.D. (2007). Tinsel town as teacher: Hollywood films in the high school classroom. The History Teacher, 40(3), 303-330.

Marcus, A.S. (2005). “It is as it was”: Feature film in the history classroom. The Social Studies, 96(2), 61-67.

Raack, R.J. (1983). Historiography as cinematography: A prolegomenon to film work for historians. Journal of Contemporary History, 18(3), 411-438.

Rosenstone, R.A. (1995). Revisioning history: Film and the construction of a new past. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Rosenstone, R.A. (1998). History in images/history in words: Reflections on the possibility of really putting history onto film. The American Historical Review, 93(5), 1173-1185.

Walker, T.R. (2006). Historical literacy: Reading history through film. The Social Studies, 97(1), 30-34.

Weinstein, P.B. (2001). Movies as the gateway to history: the history and film project. The History Teacher, 35(1), 27-48.

White, H. (1988). Historiography and historiophoty. The American Historical Review, 93(5), 1193-1199.

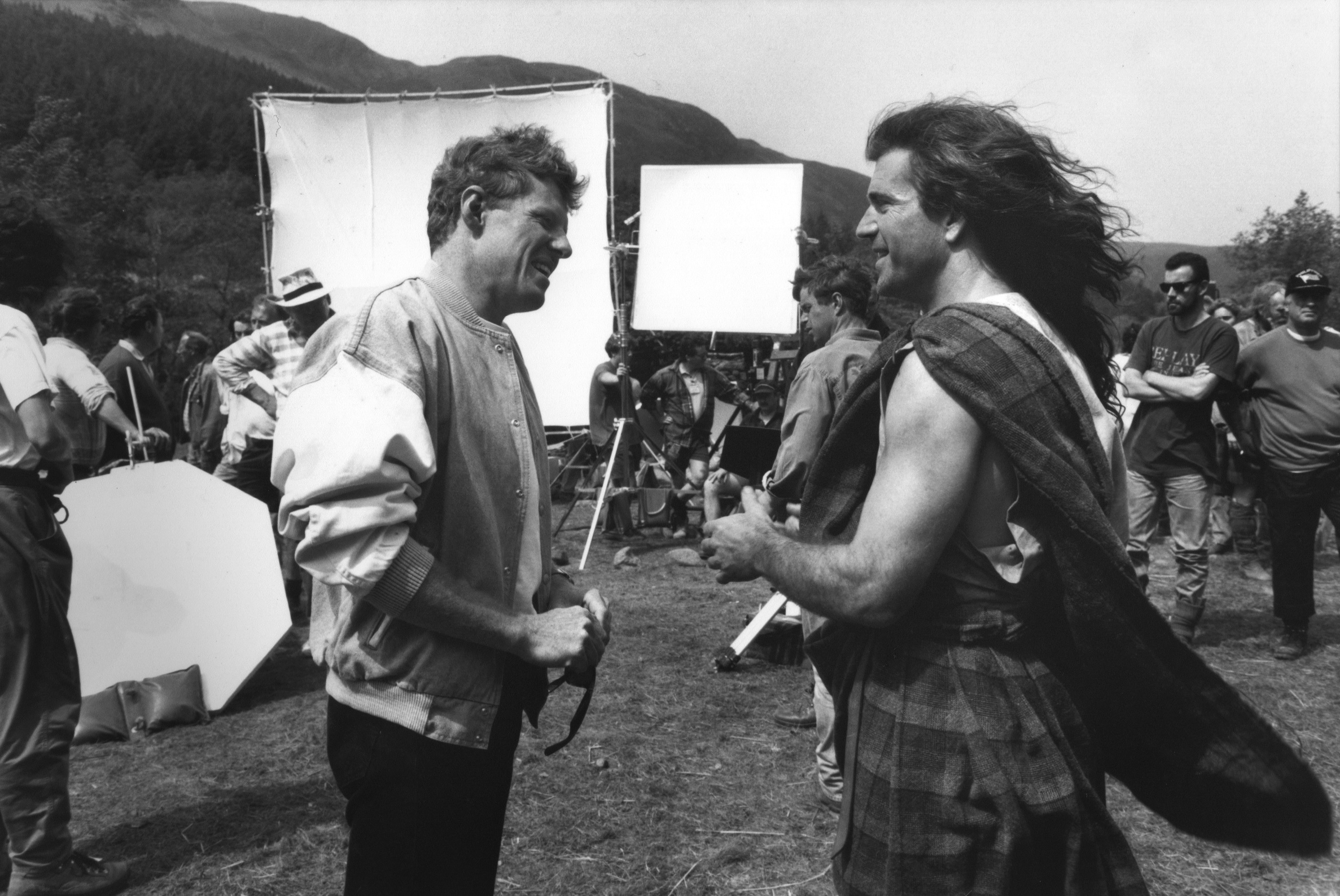

Photo credit: Set of movie "Braveheart". Wikimedia Commons.

- Se connecter ou créer un compte pour soumettre des commentaires