Family History as a Gateway to Learning about Archives

20 December 2013 - 1:02pm

This monthTHEN/HIER has seen a number of thought-provoking blog posts about the role that family history plays in the life of both the student and the teacher. Heather McGregor wrote an excellent blog about how family history is useful because it helps us to foster an ongoing relationship with the past, making history more meaningful and relevant to generations of budding historians. Covering family history in the classroom allows learning to go beyond the textbook and opens the door of possibility for building research skills early in education. As mentioned by Heather, it can often be difficult to translate the passion that an educator feels for history into a classroom lesson or activity that is engaging for the student, who may not feel that same passion. Family history is an exceptional bridging tool with which children and young adults can connect, providing the opportunity to teach effective research skills in a creative way.

This monthTHEN/HIER has seen a number of thought-provoking blog posts about the role that family history plays in the life of both the student and the teacher. Heather McGregor wrote an excellent blog about how family history is useful because it helps us to foster an ongoing relationship with the past, making history more meaningful and relevant to generations of budding historians. Covering family history in the classroom allows learning to go beyond the textbook and opens the door of possibility for building research skills early in education. As mentioned by Heather, it can often be difficult to translate the passion that an educator feels for history into a classroom lesson or activity that is engaging for the student, who may not feel that same passion. Family history is an exceptional bridging tool with which children and young adults can connect, providing the opportunity to teach effective research skills in a creative way.

As a student of history, I often found the concept of the archive to be illusive. Archives were not mentioned by instructors until post-secondary education, at which point the word was dropped as if all students were expected to know what kind of material to find in an archive and how to go about the daunting task of performing archival research. Next came the awkward dance of trying my very best to complete research assignments while avoiding the intimating and unfamiliar concept of the archive – and it turned out that this is something that you cannot, and should not, avoid in university.

It was not until my fourth year of undergraduate studies that a professor brought one of my seminars to the Queen’s University Archives and showed us what kinds of materials we could expect to locate in an archive, and how to go about finding it. From that point on, archives have been remained an invaluable resource in my life. Knowing the kinds of treasures that an archive can hold, and more importantly how to access this material, would have been incredibly useful earlier in my education. Incorporating family history in the classroom allows teachers to introduce students to archives in an intellectually accessible manner. Archives are not necessarily dusty and inaccessible; rather, some archives have cultivated impressive online presences that allow students to visit collections from their home and prepare for their post-secondary educations.

During my graduate degree, an instructor used reference exercises in an “Archives in the Digital Age” class as a means to familiarize students with the process of using genealogical databases online. This teaching method was incredibly effective: the students became excited and engaged with the activity, which felt like an academic scavenger hunt. The activity involved small hints worked into a sample inquiry from a fabricated archives visitor. Students were tasked with slowly pieced together the details of a stranger’s life. Library and Archives Canada provided access to a plethora of information, allowing us to locate military, burial, and census records. This type of activity can be adapted for classrooms of many different ages, and is a great way to introduce students to primary sources and the process of using archives.

Resources for reference activities:

The Connecticut State Library created this listing of 18th and 19th century nicknames, which is an interesting way to introduce the topic of family histories and primary records in a younger classroom.

Archeion is a service run by the Archives Association of Ontario, which compiles records from archival organizations from all across Ontario. The website allows you to search by subject, place, and type of digital record.

The Canadian Virtual War Memorial provides information on veterans, which includes birth dates, position titles, and burial records. Burial information is provided by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission , a resource that allows the user to search by soldier’s name or by cemeteries across 153 countries.

The Soldiers of the First World War (CEF) Database is searchable by surname, given name, and regimental number(s). The results provide regiment numbers and digitized attestation papers if available, which include: date of birth, place of birth, religion, trade, and a physical description.

Lastly, Library and Archives Canada has a genealogy section, including a youth corner, which teaches the user how to start, strategies for locating different types of information, and how to organize the archival results. The types of records available include: birth, marriage, death, census, immigration, and land records.

How else can family history be taught in the classroom?

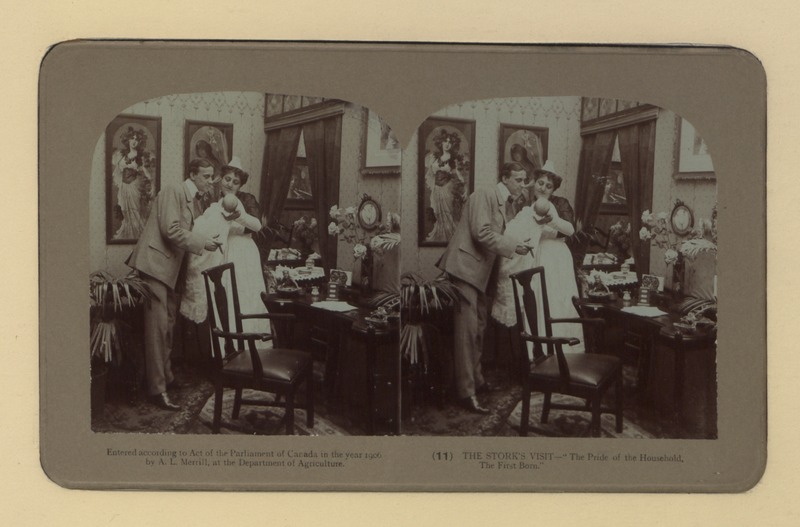

Photo: Courtship and Wedding: The Stork’s Visit, Canada, 1906. British Library, Accession number HS85/10/17208, copyright expired, Wikipedia Commons.

- Se connecter ou créer un compte pour soumettre des commentaires